Our dominant visual imagery of money and banking is inaccurate and continues to perpetuate myths that shield banks from greater scrutiny. This article Brett Scott sketches out a project to build the world’s first stock imagery site dedicated to presenting critical, alternative takes on the reality of money and banking.

If you type ‘money’ into Google image search, you get the following:

What’s the problem here? These images don’t show money. They show a particular form of money called cash. These ‘bearer instruments’ that we carry around are a small percentage of the money in circulation. The majority of our money is not in the form of cash. It is digital. This means it exists on databases maintained by commercial banks. But, what happens if you type ‘digital money’ into a Google image search?

Well, the dominant paradigm is to show cash flying through some kind of Matrix, or dissolving into data, or – as in one of the images above – a human hand sticking out of a computer holding cash. They’re still fixated with cash, as if cash is the original money and everything else is a variant of it or a deviation away from it. It’s not just Google images that does this. The world’s top stock image companies all fixate upon cash. Here’s the ‘money’ page from Getty Images:

For some, this imagery is unproblematic. Who cares if we use cash as the basis to represent all money? It is, however, deeply problematic. Firstly, it is inaccurate, which we might argue is a good enough reason to change it. And not only is it currently inaccurate, but it’s always been inaccurate. Physical cash forms of money have always existed alongside non-physical forms of ‘ledger’ money. More important than pedantic intellectual accuracy, though, is the fact that this imagery helps to maintain a false paradigm about what the financial sector is and what it does, and this false paradigm is one of the ways that banks can avoid political scrutiny for their actions.

We live with an economic folktale that goes as follows: Money is a ‘thing-like’ commodity and banks are intermediaries that move it around. You ‘put it into’ your bank account, and then you can ‘transfer’ it to others, or the banks can ‘lend it to others’. This idea that money is stored and passed around like a normal object is one of the great myths of finance, and an extraordinary number of people take it for granted, including business school professors, economic journalists, and parents and schoolteachers around the world who continue to pass the myth on to generations of children. And everyday this myth gets perpetuated via the images we see in the press.

So what is the alternative story? Money is not a commodity, and never really has been. Furthermore, in its current form it cannot exist without banks. Most of the money we use is not state money, but privately issued commercial bank money. Banks are not mere intermediaries in the background. They are a crucial pillar of the entire exchange system upon which we rely. This system grants them extraordinary creative and destructive power, and it is power that needs to be monitored. Unless we can see the underlying basis of the monetary system clearly, we will struggle to do this.

CALL FOR IMAGES 1: VALUE VS. MONEY

The vast majority of monetary imagery – regardless of whether it attempts to show cash or digital money – essentially fixates on the ‘object’ of money, rather than the system of value that underpins it. Is this important, and how would we change it?

The fact that ‘money’ is a noun suggests that it is an ‘object’. But what is that ‘object’? The first thing we know is that the object is defined by numbers. $200 is numbers, but numbers of what? Numbers are supposed to convey units of something. Zero represents nothingness, and one represents the base unit of somethingness, and then the multiples of one show how many units of somethingness I have. But what is this somethingness? What is £300? If you ask people to visualise $20 they tend to immediately imagine a cash note with $20 on it, but they are just ‘kicking the can down the road’. What do the numbers actually mean?

Many people have often wished to imagine that the numbers literally are value. This is 20 units of actual value that can be passed around like a commodity. That ‘intrinsic’ value can either be imagined in the form of utility – the money is useful in itself, like a chocolate dollar you can eat – or in the form of labour, like Adam Smith and Karl Marx did, where they imagined it as somehow being an embodiment of embedded previous labour, captured or ‘stored’ in the units of money.

The idea that somehow the money is units of value is extremely dubious though. Thinking that money ‘stores’ value is a bit like imagining that a Starbucks voucher stores coffee. This is why many have chosen to think that perhaps money is not actual value, but a kind of representation of value, a symbol of it, or an avatar for it. Many representations in the world, though, have no active power – holding a picture of Donald Trump does not mean you get to meet him. It is merely a representation. Money might represent value, but more importantly, it allows you to gain access to value. It seems to be a kind of portal to human labour, or an access key that unlocks it.

In its most basic sense, money appears to be a claim upon human labour that we can use to mobilise human labour. I walk into a cafe and use it to mobilise the barista to make me a coffee. This is a monetary exchange. Essentially I get a specific good or service, created through the specific labour of specific people, by presenting a token that grants access to general goods and services created through the labour of people in general. The person who holds a money claim, in other words, has a claim upon the labour of people in general. This claim has a certain magnitude. The more you have, the more ability you have to control labour.

There is debate about what gives this claim its power. One angle of thinking is that we all collectively trust in it. I accept money because I believe others will accept it from me. We thus construct its legitimacy through some kind of social agreement. Another line of thinking is that we are forced by an external authority like The State to view it as legitimate. Thus, we only use it because we are forced to pay taxes in it, for example.

There is a more subtle line of thinking though. Note that the labour being mobilised in the example above is specifically the barista, but for this situation to exist there were thousands of previous acts of labour to grow, process, pack and transport the coffee beans and to create the machines used to make the final coffee. Money systems thrive in these situations where labour is highly specialised. This is a key element of what locks money systems into human labour. In a situation where one cannot survive without the production of other people, you crucially need a generic representation of the link between your specialised labour and the general pool of labour of other people. Money tokens come to form that link – on the one hand they represent ‘what I earned for what I did’, but that only makes sense when paired with ‘what I can get from other people’, because what you ‘earned’ is the ability to command goods and services from others.

Perhaps the power of modern money is established through a combination of state power, societal agreement and the coercive network effects of being utterly dependent on the labour of others. Thus it comes to function as an access key to the labour of a huge body of strangers who are all reciprocally locked into dependence on each other. We are forced to accept it because we cannot survive without accepting it.

BRIEF 2: CASH vs. LEDGER MONEY vs. DIGITAL LEDGER MONEY

So let’s say we agree that money is some kind of claim, token, access key or representation that gives you access to value produced by other people. You have two choices about how to record that claim. You either imprint it on a physical object, or you write it down in a ledger. The key initial point is that a token or claim needn’t be embedded in a discrete physical object. It can take the form of a data entry, or ‘data object’.

For much of monetary history, ‘ledger’ money has been as important as cash forms of money. Ledger money essentially takes the form of data entries in a ledger, attributed to accounts representing particular people. An authority controls the ledger, and edits it, and has power to alter the monetary balances in response to either commands or requests from the account holders, or through political powers granted to the ledger-keeper (such as the credit creation power that banks have in which they can write new money into existence in accounts)

Note the components here

- Ledger: An ordered database with allotted spaces – accounts – in which you can record account balances and changes to account balances (‘transactions’)

- Account: A space on a database attached (or attributed to) a particular person, either a natural person (real human being), or a corporate person (a collective legal entity)

- Account holder: A person who the account represents, and who ‘owns’ the account, and who has rights to request changes to it

- Account balance: A number attached to an account, representing the number of monetary tokens attributable to the holder of the account

- ‘Keeper of the ledger’, or the recording authority: The entity that holds and controls the ledger, is authorised to make changes to it, and is responsible for maintaining its integrity

Here is an example of an old banking ledger, used by the keeper of the ledger to ‘keep score’ of money tokens in the accounts of account-holders

The ledger keeper is supposed to abide by information-recording protocols that maintain the validity or the reliability of the recordings. This means the ledger keeper is not supposed to make arbitrary changes to the data on the ledger, and must have some reason to do it, or be abiding by a set of rules. For example, if an account holder requests to ‘transfer $356’ and the ledger keeper instead decides to edit their account to reflect a negative change of $678, this is a breach of the information protocols that keep the data valid. The account holder will shout at them until they re-edit the system.

It is these information rules that help to establish the idea of the data being subject to restrictions that prevent it arbitrarily expanding, altering or morphing. It is these restrictions that help create the sense that the data is an ‘object’, rather than mere information. Rather than being arbitrarily changeable, there must be both rules for the 1) creation of data, or its initial recording and 2) altering of previously created recordings of data.

We often imagine our digital money in our bank account as a ‘data object’ that can be ‘moved around’. The term ‘movement’ in these systems, though, is essentially a metaphor, because there is no actual physical movement of monetary tokens. In a ledger system there is only simultaneous editing of two account entries that creates a positive and negative change to the respective balances. This mimics the physical process of ‘taking money from one person and giving it to another’, and thus creates a residual impression of the money having ‘moved’. To date all visual imagery around digital money continually replicates the movement analogy, for example by showing cash notes flying through a fibre optic cable. In reality, though, the only thing that really ‘moves’ in the system are packets of information between the holders of accounts and the keepers of databases, notifying the keepers to edit account balances.

Components of ledger money

Ledger money is composed of four basic components

- A ledger, which is a database of account balances and transactions

- A recording technology: A means to write things into that ledger

- A recording agent: The agent that writes things into the ledger, or edits them

- A communications system that connects with it, enabling the holder of the account to request edits to the ledger, or make queries about the current state of the ledger

Note the two following examples: A person walks into an old bank and talks (communication system) to a clerk (recording agent) with an old ledger book (database ledger) and quill pen (recording technology). This is conceptually the same as a person sending a message via their mobile phone (communication system) to a bank database system (database ledger) that utilises automated hardware (recording agent) to imprint atoms representing binary code (recording technology) on a hard-drive.

| Ledger |

Recording tech |

Recording agent |

Comms system |

| Ledger book |

Pen |

Clerk |

Speech |

| Computer database |

Magnetised atoms |

Automated rule system and hardware |

Mobile phone |

Components of digital ledger money

Digital money is a particular implementation of ledger money in which the recording takes the form of atomic structures imprinted on hard drive materials that are interpreted as binary code. The data is arranged into categories like ‘accounts’ and ‘balances’ – i.e. Account number 25672 has a balance of £4687, and these balances are supposed to reflect the net result of ‘transactions’ – i.e. Account 25672 had £4000, but then received £687 and the net result is that the new balance is £4687. These transactions are delivered into the system via multiple communications infrastructures, including

- A person walking into a branch and asking the clerk to communicate it to the system

- Internet banking portals

- Mobile phone banking

- Credit card networks for point-of-sale interactions

- The ATM network

- The cheque clearing infrastructure

Imagery of Money as Data

In terms of imagery, this opens up a number of areas we can explore. How does one ‘see’ a database? In the old days it was simple – it was literally a book. Nowadays it is harder.

Binary code?

Entries in databases – or data objects – used to be created with strokes of a quill pen. Nowadays though, we use binary code… or do we? Actually we use atomic structures imprinted on hard drives, which is then interpreted as binary code. Can you show money with binary code, or is that like zooming in on the drying ink on an old ledger book?

The datacentres

Perhaps rather than the atomic microstructure of account entries, we look at the whole ‘ledger book’, which in modern times takes the form of datacentres. How do these look? Does a bank datacentre look anything different from any other datacentre? And if not, how would showing a datacentre convey anything about money in particular? Are datacentre images essentially about conveying a visual representation of data more generally, or can they somehow be used to convey the idea of ‘money as data’?

The controller of the datacentre

It makes a difference who controls the arrays of databases. They are run by large banks. Here is an image – at least in theory – of a datacentre run by Barclays Bank in the UK:

The network of bank and central bank databases

Money systems, though, are larger than just single banks running datacentres. They operate as networks of different bank datacentres communicating with both their customers and each other via various protocols. They are all connected into the central bank datacentres too. This is where we get into the deep essence of money systems. The money system has layers of accounts – the commercial banks have reserve accounts at the central bank, and it is against the backdrop of these that they set up accounts for ordinary people.

Accounting tables

The bank datacentres are essentially tools for accounting. We might experience the data in our bank account as ‘something we have’, but to they bank it is something they’ve promised. It is essentially a liability for them, set against their assets at the central bank. We might simplify this by drawing accounting tables. In the image below we merge datacentre imagery with accounting tables and Bank Logos:

The international network

We can then start to internationalise this. The UK pound data ecosystem interacts with all the other currencies around the world via international financial data exchange protocols and the correspondent bank network. This starts to get very complex to represent.

Returning to the problem of the ‘movement’ metaphor

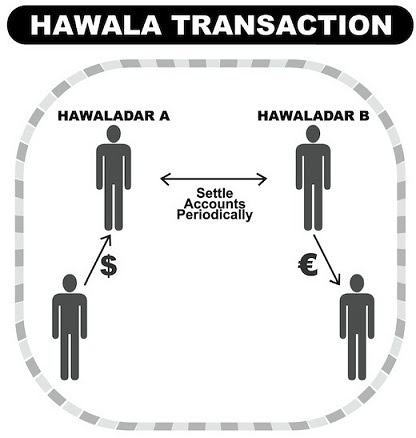

When we start to see the international monetary system as essentially an accounting system hosted by banks controlling data recording and communications infrastructures, it becomes apparent that money ‘movement’ is essentially the act of banks coordinating the editing of multiple databases. The ‘clearing and settlement’ system is essentially the mechanism that tries to reconcile the various changes that need to be made to all the various databases.

The term ‘movement’ implies the idea of a coherent object that moves from one place to another. And yet it is not the same ‘object’ that moves. The unit of money that is deleted from one person’s account is not the unit of money that is recorded into another’s. The unit that is deleted represents the retraction of an old promise by the bank. The unit that is recorded represents the giving of a new promise by another bank. The promises of those two banks are not ‘fungible’. They are not the same thing. Nothing has ‘moved’. All the moved was light beams in fibre optic cables or electrons in wires conveying messages to reconfigure the balance of obligations promised by various parties to each other.

The physical communications infrastructure

We might choose to look rather at the communication channels. Below is Femke Herregraven’s Cable Landings, showing the landing points of fibre optic cables used for financial communications:

Image brief 3: Moving beyond money as mere data

There is a problem with ‘money-as-data’ approaches though. Anyone can set up a series of databases, and say that the information recorded on it represents legitimate money tokens, but would we ever believe them? In reality, money is not merely data. It is data recorded in a particular political and social context by authorities deemed to be legitimate.

If a bank records money into existence, we view it as ‘real’, whereas if a local anarchist collective does it, we may see what they have recorded is ‘meaningless data’, like the scribblings of a child in a old book, pretending that they’re a banker. The realness of data objects – or perhaps the ability to view data as a ‘real object’ – comes when the creator of the data has the power to ‘make it real’, such that what they write down has real world impacts, can mobilise people, and has legal backing. Let’s take an everyday situation of monetary exchange at a health spa: we can characterise it as ‘if you change a data entry I will give you a back massage’. The data itself cannot ‘act on someone’, or make them do something, so for an act of data recording to have an activating power upon the masseuse, and to thereby make them ‘do something for me’, it must be set within a political system, a particular social situation that makes people act of the data, or a cultural belief system that gives it power.

Western Union is a financial service and communication company from the US which is mostly known for transferring money. In the 19th Century Western Union dominated the telegraph industry in the United States. Nowadays it is the biggest player in transferring the remittances of migrant workers all over the world.

Western Union is a financial service and communication company from the US which is mostly known for transferring money. In the 19th Century Western Union dominated the telegraph industry in the United States. Nowadays it is the biggest player in transferring the remittances of migrant workers all over the world.