What Is Anonymity?

The term „anonymity“ comes from the Greek word „anonymia“ (ἀνωνυμία), meaning „without a name“ and its contemporary use has more or less kept this original definition. Often, however, the term refers to the sorts of protection that non-identity provides. In the internet environment, where we are learning that every action may be tracked, traced, and stored for an indefinite amount of time, the term has taken on new weight and become the center of a great deal of controversy and debate.

The dominant narrative of anonymity, as portrayed in popular media, is an unflattering one and its usage is associated with trolling, seedy transactions, harassment and terrorism. The conventional wisdom seems to be that online anonymity protects criminals and enables the hateful and toxic side of human nature. Such a negative reputation undermines an important practice with many legitimate uses. Anonymity can also offer vital protection to those who need it most.

For many individuals trapped in asymmetric relationships, whether with an abusive spouse or an oppressive state, identity can become a vulnerability. For the activist under a violent regime or the victim of online harassment and threats, the absence of their true name may be all that’s ensuring their safety. More innocently, anonymity can also provide a necessary space for the mistakes and regrets that come with personal exploration and growth. It can also allow us to explore new identities, relationships and communities.

In the case of journalism, anonymity is a fundamental tool. Many journalistic practices rely on it: be it the protection of sources or freedom of expression.

Anonymity In Journalism

Anonymity has a critical role in journalism in general, and it’s no different for digital communities built around news sites and other journalistic services. Numerous news communities have developed real-name policies based on the assumption that people’s behaviour and speech will be more respectful and generative if they are forced to use their „real-world“ identities. Of course, the problem is that many people are proud of their opinions, no matter how terrible others think these may be.

In general, such policies hurt people who have legitimate reasons for anonymity. Some personal anecdotes may be important to share, but they also might be damaging if traced back to someone specific. Perhaps someone wants to contribute some insider knowledge of how a company operates, but needs to keep their job. There are many scenarios like this.

Anonymity in Practice

The situation in Belarus

By the end of 2014 Belarus counted over 5 million Internet users, constituting 70% of the population aged 15 to 74. Anonymity for Belarusian journalists and users remains important, but at the same time anonymity is not an everyday need for all its citizens.

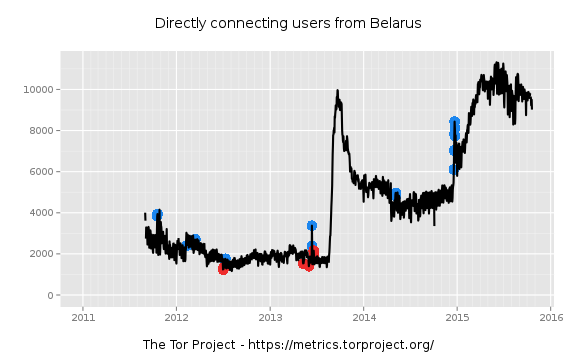

On 20 December 2014, several independent news sites were blocked by the government in Belarus. This included Naviny.by, Charter97.org, belaruspartizan.org, UDF.by, gazetaby.com, onliner.by and the website of BelaPAN, the only independent news agency in the country. Several days later the leading Belarusian news portals published articles explaining how to access blocked sites.

In late December 2014, several independent news sites were blocked in Belarus by the government. In reaction, online media started informing readers on how to access blocked sites. Use of Tor spiked.

A month later the country’s Communications Ministry published a new decree that mandated that internet providers limit access to certain online resources. Some of the limitations deal directly with anonymizing services. One should also take into consideration that people who are just searching for tools like Tor on the web can easily get on a NSA watchlist, as interent pioneer Konrad Becker pointed out.

34Mag.net and CityDog.by

The following two examples demonstrate how anonymity requirements can vary in a country such as Belarus. One magazine (34Mag) needs anonymity for its writers in order to do its work without being shut down and censored by the government. The other (CityDog.by) can operate without any anonymity.

34Mag, a non-commercial media organization in Belarus, produces youth publications on compact discs and the 34Mag.net website. The overall objective of 34Mag is to promote freedom of speech, creative expression, independent thought, and to foster civic activism and solidarity among young Belarusians. It does so by providing them with objective information about youth issues, broadcasting challenges and opportunities in the country and serving as a platform for youth expressing alternative opinions.

34Mag has been published since 1998. In November 2005, the last hard-copy issue was seized by the police on the pretext that it was being printed with „poisonous ink“. The magazine was banned and a criminal case was launched against the editor-in-chief. The publication’s response was to change the name and transform the publication into a multimedia edition on compact disc and an online magazine. From that moment 34Mag’s journalists stopped using their real names for security reasons.

But anonymity plays a different role for other kinds of publications. CityDog, a Minsk city digital magazine, has a special focus on fostering a sense of identity, community and civic engagement among its readers. It takes an active stance in the capital city’s life, introducing new ideas, profiling urban activists and promoting the concept of creating a “city for the people and by the people.”

CityDog is all about people. It has a personal touch, telling stories and tales of both famous and less-known city heroes. They therefore try to avoid anonymity. Yet, in some cases, when their sources prefer to stay anonymous, they respect their will.

34Mag and CityDog cover some of the same topics. But the way CityDog presents these issues might seem less „oppositional“ than 34Mag. Freedom of speech depends not only on the topics which are covered by the media but also how they are approached.

The situation in France

France used to be called the „country of human rights“. But during the last ten years it fell twenty places in Reporters Without Borders‘ annual World Press Freedom Index. Since 2001, following the United States‘ example, different levels of French governments have passed many laws reinforcing the powers of the police and surveillance agencies. This year the country re-gained one rank in the Press Freedom Index and accessed the 38th place, but this index was made before the Charlie Hebdo attacks of last January.

Since then, the government has introduced two new surveillance bills. The first, the “intelligence law”, reinforces the intelligence agencies‘ powers and their capabilities for intercepting communications and metadata without requiring permission from a judge. The second, the “international surveillance law”, which is set to be passed before the end of 2015, authorizes the mass collection of data related to international communications.

In France, a 2010 court ruling confirmed that the protection of sources is an obligation for journalists. But this principle has been subject to many attacks. In 2015 several professional associations of lawyers and journalists filed complaints before the European Court of Human Rights protesting the many surveillance laws passed in France in recent years, arguing that they violate their right to professional secrecy.

In France websites have the legal obligation to keep all the user’s metadata for one year. If legal action is taken against a user, the police can force the website to identify them. The general perception of anonymity is rather complex: An opinion poll investigated the perception of online anonymity among people of various age groups.

The main conclusion of the survey is that people tend to recognize both negative and positive consequences of online anonymity. On the one hand online anonymity – according to the survey sample – risks to encourage hate speech and is a danger for society, on the other it guarantees freedom of speech.

Mediapart

Mediapart was founded in 2008 by a group of journalists coming from Le Monde, the leading newspaper in France. Their idea was to create a news website with an editorial line contrary to mainstream trends. Back then most of the online press in France was free, up-to-the-minute and funded by advertising. Mediapart, which specializes in investigative journalism was the first online news media outlet in France to use a paywall and have no advertising. Its income is generated only through subscription fees.

The website is divided into two parts. “Le Journal,” the news section, is written only by journalists and is accessible only through a subscription. “Le Club” is participatory: Each subscriber has their own editorial space with a blog, an internal email service and the ability to comment on and discuss articles. This section is freely accessible and often has a larger audience than “Le Journal”.

Mediapart has 120,000 subscribers, more than 2.5 million unique visitors each month and publishes about 110 blog posts each day. In 2011, Mediapart also launched FrenchLeaks, a platform inspired by WikiLeaks that allows people people to anonymously send information and documents.

Over the last seven years Mediapart has revealed several major political scandals, inlcuding “l’affaire Bettencourt” in 2010, related to the funding of the former French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidential campaign. In 2012, the website also revealed that the French finance minister, Jérôme Cahuzac, had a secret bank account in Switzerland for more than 20 years.

During this scandal, which lasted several weeks, one whistleblower emerged among Mediapart’s subscribers. He was a former agent from the French anti-money-laundering agency “Tracfin.” He, however, did not contact the editorial team, but instead wrote two posts under his subscriber’s pseudonym on his blog. There he revealed some confidential information and accused his superiors of reacting too slowly to the case.

Tracfin filed a complaint for violation of professional secrecy and Mediapart soon received a decree ordering them to identify its blogger, which they did. The former Tracfin agent was prosecuted in May 2014 and sentenced to 2 months of prison on probation. Edwy Plenel, editor-in-chief, describes this case here:

This case shows that there is no absolute anonymity in France to protect these kind of sources.

Can We Really Be Anonymous?

Anonymity remains an important tool. But whether or not we can actually be anonymous is increasingly a question of policy and law. The technology which enables anonymity is widely available and, with a proliferation of user-friendly tools, is becoming more and more accessible to less-technical users.

However, armed with the rhetoric of anonymity as a tool for illegal activity, governments are actively undermining this accessibility, replacing what were once technical barriers with legal ones. What can be done to dissuade this kind of legislation? How can anonymity be recognized as an important common good?

These questions of anonymity’s status remain open, but the technical capacity for individual namelessness has arrived. The tools for protecting identity online should be of concern to any internet user.

The toolkit below gives a brief overview of where to get started. Perhaps the widespread use of anonymity can help demonstrate the misconceptions and dangers of anti-anonymity legislation.

Anonymity Toolkit

How to stay anonymous while…

- Browsing: Use encryption and anonymity tools for surfing like a VPN and/or TOR and use privacy-friendly search engines like Ixquick, DuckDuckGo or Startpage. However, once you login to a site that is connected to your identity, you are compromising your anonymity.

- Communicating: Use Jabber and OTR for secure chatting (you can use an extra jabber account) and encrypt your emails with PGP/GPG. The Free Software Foundation provides a good guide on email encryption.

- Publishing/Commenting: Submit documents using encryption (you can use PGP/GPG) and use fake names and fake/temporary email addresses.

- Sharing files: Use software like securedrop.org and globalleaks.org. These provide ways of securely receiving documents from anonymous sources.

For more comprehensive guides on security for journalists, The Centre for Investigative Journalism’s Information Security for Journalists is worth reviewing, as well Security in-a-box, a project of Tactical Technology Collective and Front Line Defenders and the EFF’s Surveillance Self-Defense resources.

Hosting an anonymous community

If you are hosting a news community, you may want to support anonymous commenting. To do so, you should allow comments to be posted without requiring any personal information (such as emails or names), but for complete anonymity, you can also avoid keeping server logs and provide access through a Tor hidden server.

A common concern is that anonymous comments will prevent civil discourse, but this is not necessarily so. To promote civil discourse, make your platform’s rules of netiquette and community guidelines explicit and enforce them with transparency.

Credits

This project was collaboratively created by Jérôme Hourdeaux (mediapart.fr), Valentin Ihßen (Universität Witten/Herdecke), Joseph Ketelhut (TU Ilmenau), Inga Lirenkadan (34Mag), Lejla Medanhodzic (AWID Women’s rights), Katerina Michailidi (BookSprints), Sara Moreira (Moving Cause), Jacopo Ottaviani (GenerationE), Cristina Pombo (Expresso) and Kavya Sukumar (Vox.com) at the UN|COMMONS conference hosted by Berliner Gazette in 2015.

Editors

Magdalena Taube (berlinergazette.de) and Francis Tseng (The Coral Project)

References (selection)

Allen, D. S. (2008). The trouble with transparency: The challenge of doing journalism ethics in a surveillance society. Journalism studies, 9(3), 323-340.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14616700801997224

Electronic Frontier Foundation. (2015). Surveillance Self-Defense. SSD.EFF.ORG. Retrieved 2015, from https://ssd.eff.org/en

Erjavec, K., & Kovačič, M. P. (2012). “You Don’t Understand, This is a New War!” Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites‘ Comments. Mass Communication and Society, 15(6), 899-920.

Front Line Defenders. (2014). Security in a Box. Securityinabox.Org. Retrieved 2015, from https://securityinabox.org/en

Manaev, O. (2014). Media in post-Soviet Belarus: Between democratization and reinforcing authoritarianism. Demokratizatsiya, 22(2), 207. https://demokratizatsiya.pub/archives/22_2_F630177066T87389.pdf

Images

The chapter images are taken from the photography project NOFAC.ES by Mario Sixtus. The are licensend under Creative Commons BY NC SA. Video icons from Noun Project by Wilson Joseph, artworkbean, Antonio Makriyannis and Igor Yanovsky. All text, info graphics and images are (if not statet otherwise) under Creative Commons CC BY NC SA.